Inference and the Boundaries of Science

AUTHOR: Hannah Maxson

SOURCE: Evolution and Design

COMMENTARY: Allen MacNeill

The now-notorious Cornell "evolution and design seminar" met for the first time last night, and in my opinion our first meeting was a rousing success. As I had hoped, the participants began to make their opinions and positions known (despite my blathering), and a good time was had by all. We're getting ready to analyze Richard Dawkins' arguments in The Blind Watchmaker, discussion of which will be facilitated by Will Provine (one of our faculty participants).For a brief taste of how things went last night, you should check out the course blog. Here's a sample:

Hannah Maxson (founder of the Cornell IDEA Club) wrote:

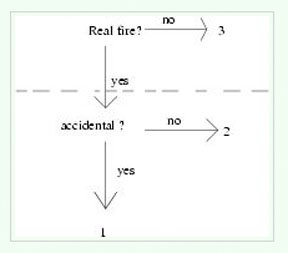

In class last night Allen went over inference and his views of the boundaries of science. He gave us the example of an individual coming upon the remains of what appeared to have been a house fire in the past. Without any prior knowledge of the event or eyewitnesses to question, one might infer any of three things (see diagram, above):

1) accidental house fire

2) arson: purposeful house fire

3) no fire at all; setup job (for film, etc.)

A tentative explanatory filter with which to distinguish between those three causes. But he suggested there is a problem from the very beginning. The first question– was this a real fire, or a setup job? can never be definitely answered. Considering a very powerful film crew, for instance, the setup would look almost like a real fire. Extrapolating slightly, given an omnipotent “designer”, could the scene not be exactly the same as what one would expect from a housefire?

Because there is no way of giving a definite answer based on empirical evidence– to which we, as scientists, are limited– we must throw out that whole node on our explanatory filter. Everything above the dotted line, at least, is outside our realm of knowledge.

I had a quarrel with much of this reasoning, though to begin with I ought to make a strong disclaimer that I’m not at all interested in defending “setup jobs”– I think they are highly uninteresting, for one thing, and not worth spending time in. But a “right” or at least convenient answer doesn’t make the logic that goes into an argument sound.

First, can we throw a question out of the realm of science because we will never be able to get a definite answer? Scarcely anything in science will ever be proved or disproved. In general, we don’t look for certain proofs, but simply for empirical evidence that might favor one or the other, so that we can make an inference to the best explanation. If the evidence is not clear, we often make choices based on conventions, such as parsimony.

If we cannot throw it out for lack of a definite answer, can we at least throw out that node for lack of empirical evidence either way? It is true that if the scene was designed (omnipotently) so that there was absolutely no evidence there had been no real fire, science could do nothing with the question. But we cannot assume a priori that all “setup jobs” have no emperical evidence available; there are a great many other possibilities besides an omnipotent designer who works to make things exactly the same. Consider, for example Einstein’s view: “Nature hides her secrets because of her essential loftiness, but not by means of ruse.”; or in another remark: “God is slick, but he ain’t mean.”

So while we can do away with a “absolutely perfect imitation” possibility as an option that could never have any emperical grounds, that is not justification for demarcating the entire first node out of our field of inquiry. In any research project you learn quickly that things are not always as they first appear. What seems on first analysis to be the remains of a fire may turn out on further investigation to hold evidence of a set-up job. What appears to have been designed may in fact be the product of chance and necessity, and what we are used to thinking of as the products of unguided evolution may contain evidence of purposeful design.

Refusing to consider questions is never good practice; we may reject explanations for lack of warrant, but ought never reject the investigation a priori.

To which I replied:

Thanks, Hannah, for the diagram (it’s clearer than mine was last night) and for your analysis, above. However, I still stand by my position that, given a sufficiently powerful “designer,” a house fire (or anything else) can be simulated to such a degree (as Warren [Warren Allman, director of the Paleontological Research Institute and Museum of the Earth here in Ithaca] said, “right down to the subatomic particles) that there would be absolutely no way to distinguish between such a creation ex nihilo and the real thing.

That is, no amount of empirical evidence could make it possible to get past the first branch point in the explanatory filter in the diagram. Indeed, every piece of empirical evidence one could add would simply amplify one’s assertion of the hypothesis of the Designer’s omnipotence (”Amazing, S/He/It can f/make things right down to the quarks!”). For this reason, rather than agonize over our inability to get past the first branch point in the filter via empirical means, we simply agree to skip that step and move down to the second branch point.

I believe that this “agreement” is something with which most ID supporters would concur, as it gets us out of an empirically insoluble dilemma, and moves us along to the question of accident vs design. Darwin did essentially the same thing in the Origin of Species, by bringing in “the Creator” only at the very end, and by relegating Her/Him/It to setting the whole system in motion in the beginning. Having spent many years reading Darwin’s personal writings (correspondence mostly, but also some of the expurgated sections of his autobiography), it appears to me that Darwin became a Deist about the time he wrote the Origin (or in the process of doing so, which took two decades), but then slowly realized that Deism is essentially equivalent to agnosticism/atheism, as the Deity of Deism plays no part in the actual universe at all, beyond setting up the natural laws that govern it. I find myself in the same situation: assuming that the Deity of Deism exists gets one absolutely nowhere at all in science, and so (like most other scientists), I simply don’t go there anymore.

And now I would go further; while it is a good idea to "not reject explanations for lack of warrant, bu never reject the investigation a priori", the point I was trying to make in my reply was that if one can't get by the first branch point in the "explanatory filter" I posited during the discussion, then we can't really do science at all. Furthermore, agreeing that the remains of what looks like a house fire could have been created ex nihilo by a sufficiently powerful entity gets us absolutely nowhere in terms of explaining the origin of the wreckage. In fact, it forestalls the possibility of any kind of empirically verifiable (or falsifiable) hypothesis, and is therefore a "science stopper" of the first order.

--Allen

Labels: abduction, abductive reasoning, consilience, deduction, deductive reasoning, induction, inductive reasoning, inference, logical inference, transduction, transductive reasoning

2 Comments:

Hello!

"The first question– was this a real fire, or a setup job? can never be definitely answered. Considering a very powerful film crew, for instance, the setup would look almost like a real fire."

This is somewhat confusing. I know that the explanatory filter here isn't supposed to be William Dembski's, but Hannah as founder of the Cornell IDEA Club ought to have been aware of Dembski's filter, where you do not have a design hypothesis. In the filter presented here, the starting point is a design hypothesis, and as Hannah correctly points out, that doesn't work.

"Extrapolating slightly, given an omnipotent “designer”, could the scene not be exactly the same as what one would expect from a housefire?"

Exactly therefore. Supposedly, a sufficiently capable designer can do anything, including mimic any natural cause.

"I believe that this “agreement” is something with which most ID supporters would concur, as it gets us out of an empirically insoluble dilemma, and moves us along to the question of accident vs design."

They certainly should; but I actually fail to see the whole point - unless you are trying to explain, why Dembski has his filter turning the way it does. The first two nodes are design nodes: the setup (no real fire) and arson. Assuming design, you need to guess at what a designer can do, but as everybody agrees, designers can do everything that pleases them - assuming they are sufficiently capable.

An explanatory filter necessarily must have its nodes in increasing order of capabilities, if the capabilities required for each node cover all those above.

The explanatory filter presented here is rather confusing. Nodes should be visited in order of increasing capabilities. That is the order should have been as the numbers indicate:

--------------------------

1) accidental house fire

2) arson: purposeful house fire

3) no fire at all; setup job (for film, etc.)

--------------------------

Not as the sketch shows, with the nodes in reverse order.

A designer can pick and choose, and the designer at node 2 would attempt to mimic the accident at node 1. That is, if node 2 is visited before node 1, a false conclusion might be drawn. Likewise, the designer at node 3 certainly would try to mimic either node 1 or node 2, and therefore starting the filter with node 3 is the worst possible choice.

William Dembski's explanatory filter (which has flaws of its own) avoids these problem by not> explicitly having a design hypothesis - it uses the mantraic expression "specified complexity" instead.

So, if your purpose was to ague against Intelligent Design, you would appear´to have burned down a straw man, not an entire house ;-)

Post a Comment

<< Home