More on Evolution and Human Free Will

Every summer I teach a seminar course at Cornell in which we examine the historical, philosophical, religious, and scientific implications of evolutionary theory. This summer our seminar course will once again consider the question: Is free will an illusion?

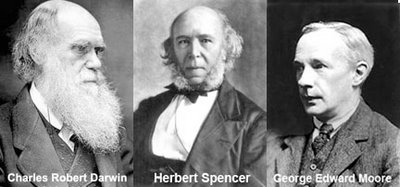

On the 15th of July, 1838, Charles Darwin began a notebook which he labeled as “M”, in which he intended to write down his correspondence, discoveries, musings, and speculations on “Metaphysics on Morals and Speculations on Expression”. On page 27 of that notebook, he wrote

“…one doubts existence of free will every action determined by hereditary constitution, example of others or teaching of others. (…man…probably the only [animal] affected by various knowledge which is not heredetary & instinctive) & the others are learnt, what they teach by the same means & therefore properly no free will. [Emphasis added]

In his private musing on the question of free will, Darwin came to the conclusion that human free will is an illusion, and that all of our actions (and, by extension, our thoughts and intentions) are the result of our “hereditary constitution” and “the example…or teaching of others.”

Some evolutionary biologists, notably William Provine of Cornell University, have followed Darwin’s lead and asserted that human free will is an illusion. Most philosophers disagree, asserting that free will is the principle difference between humans and non-human animals. Many Christian theologians go further, asserting that free will is the foundation of all human action, without which no rational ethics or theology is possible.

In our seminar course this summer we will take up this debate by considering two alternative hypotheses: (1) that human free will is real and can provide a basis for our morals and ethics, or (2) that human free will is an illusion, the capacity for which is a product of the same evolutionary processes that have shaped our anatomical and behavioral adaptations. Included in this debate will be an extended consideration of the hypothesis that the capacity for ethical decision making is an evolutionary adaptation that has evolved by natural selection. We will read from some of the leading authors on both sides of the subject, including George Ainslie, Daniel Dennett, Robert Kane, William Provine, Daniel Wegner, and Edward O. Wilson. Our intent will be to sort out the various issues at play, and to come to clarity on how those issues can be integrated into a perspective of the interplay between philosophy and the natural sciences.

Here are some particulars for the course:

INTENDED AUDIENCE: This course is intended primarily for students in biology, history, philosophy, religious studies, and science & technology studies. The approach will be interdisciplinary, and the format will consist of in-depth readings across the disciplines and discussion of the issues raised by such readings.

PREREQUISITES: None, although a knowledge of general evolutionary theory, evolutionary psychology, sociobiology, and the philosophy of human free will would be useful.

DAYS, TIMES, & PLACES: The course will meet on Tuesday and Thursday evenings from 6:00 to 9:00 PM in Mudd Hall, Room 409 (The Whittaker Seminar Room), beginning on Tuesday 29 June 2010 and ending on Thursday 5 August 2010.

CREDIT & GRADES: The course will be offered for 4 hours of credit, regardless of which course listing students choose to register for. Unless otherwise noted, course credit in BIOEE 4670 / BSOC 4471 can be used to fulfill biology/science distribution requirements and HIST 4150 / STS 4471 can be used to fulfill humanities distribution requirements (check with your college registrar's office for more information). Letter grades for this course will be based on the quality of written work on original research papers written by students, plus participation in class discussion. All participants must be registered in the Cornell Six-Week Summer Session to attend class meetings and receive credit for the course (click here for for more information and to enroll for this course). Registration will be limited to the first 18 students who enroll for credit.

REQUIRED TEXTS:

Ainslie, G. (2008) Breakdown of Will, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 0521596947 (paperback: $34.99), 272 pages.

Dennett, D. (2004) Freedom Evolves, Penguin Books, ISBN: 0142003840 (paperback: $17.00), 368 pages.

Kane, R. (2005) A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will, Oxford University Press (USA), ISBN: 019514970X (paperback: $19.95), 208 pages.

Wegner, D. (2003) The Illusion of Conscious Will, MIT Press, ISBN-10: 0262731622 (paperback: $21.95), 419 pages.

Wilson, E. O. (2004) On Human Nature (Revised Edition), Harvard University Press, ISBN: 0674016386 (paperback: $22.00), 284 pages.

OPTIONAL TEXTS:

Darwin, Charles (E. O. Wilson, ed.) (2006) From So Simple a Beginning: Darwin's Four Great Books. W. W. Norton, ISBN-10: 0393061345 (hardcover, $39.95), 1,706 pages. Available online here.

Fisher, J., Kane, R., Pereboom, D., & Vargas, M. (2007) Four Views on Free Will, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 1405134860 (paperback: $33.95), 240 pages.

Kane, R. (2001) Free Will (Blackwell Readings in Philosophy), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN: 0631221026 (paperback: $33.95), 328 pages.

Wilson, E. O. (2000) Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (25th Anniversary Edition), Belknap Press, ISBN: 0674002350 (paperback: $44.00), 720 pages

Our summer seminar course is always fascinating, and often quite controversial (see this and this). Over the years we have explored many of the implications of Darwin's theory, and the participants have always found our discussions (perhaps they should be called "debates") enlightening. As always, the intent is not necessarily to reach unanimity, but rather for each participant to come to clarity on where they stand on the issues and to be able to defend that stance using evidence and rational argument.

So, please consider taking our seminar on free will this summer - the choice is yours!

************************************************

As always, comments, criticisms, and suggestions are warmly welcomed!

--Allen

Labels: Charles Darwin, evolution, evolution and ethics, evolution and free will, free will, William Provine